Geometry of desire

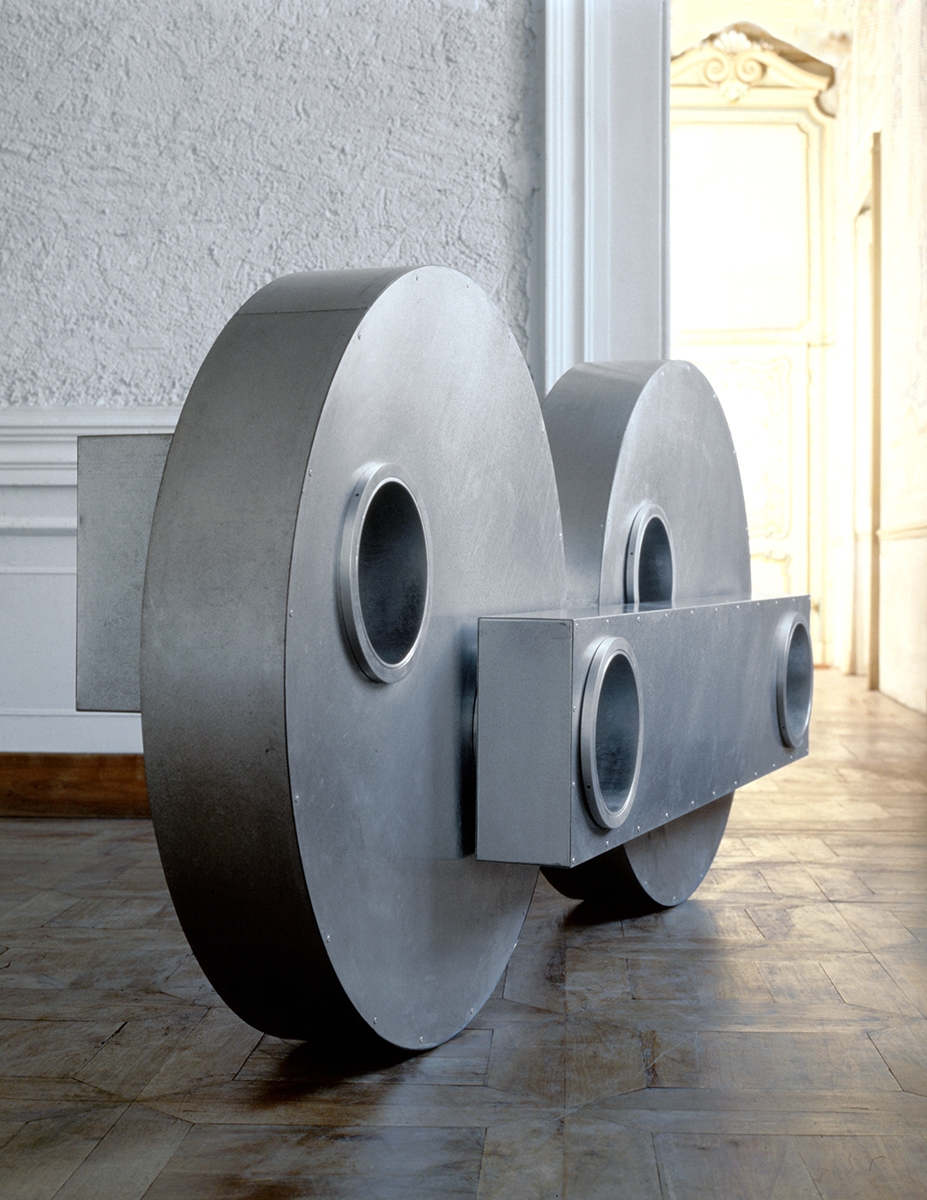

Voglia di treno, realised in 1989, is set in a crucial phase of Umberto Cavenago's career, when the artist, after his first exhibition experiences between Turin and Milan, was consolidating an autonomous language capable of emancipating sculpture from the traditional pedestal. The work was presented in significant contexts, such as the Franz Paludato Gallery in Turin and in the spaces of the Rivara Castle, and was part of a moment of progressive international recognition, culminating with his participation in the 1990 Venice Biennale.

On a conceptual level, the work interrogates the myth of progress through a formal synthesis that reduces the steam train - a 19th-century icon of speed, connection and modernity - to a minimal structure, evocative but lacking in direct function. This subtraction is not negation, but critical device: the implicit rhythm of the connecting rods and wheels becomes allusion rather than mechanics, allegory rather than technique. In the Italy of the late 1980s, suspended between economic acceleration and social contradictions, Voglia di treno highlights the ambiguity of development narratives, opening up a terrain that will be echoed in later works such as Un milione di posti di lavoro (1994), where irony becomes an instrument of social criticism. The title, with its ironic lightness, suggests a collective tension towards movement and change, but at the same time registers the difficulty, the delay, the suspension.

As an example of research, Voglia di treno shows Cavenago's ability to transform the collective memory of an everyday object into a poetic and critical device. It is not the steam train that promised progress, nor a toy that reduces the object to pure simulation: it is rather a signal, a clue, a 'desire' that manifests itself in matter and space. Sculpture thus becomes a place of questioning: about the relationship between technology and desire, between movement and stasis, between promise and irony.

Social

Contatti

umberto@cavenago.info